This article was originally published on the Lyft Engineering blog on March 25th, 2022.

Introduction

In a data-driven company like Lyft, data is the core backbone for many application components. Data analytics gives us the incentives for improving existing features and creating new ones. Today, Lyft collects and processes about 9 trillion analytical events per month, running around 750K data pipelines and 400K Spark jobs using millions of containers.

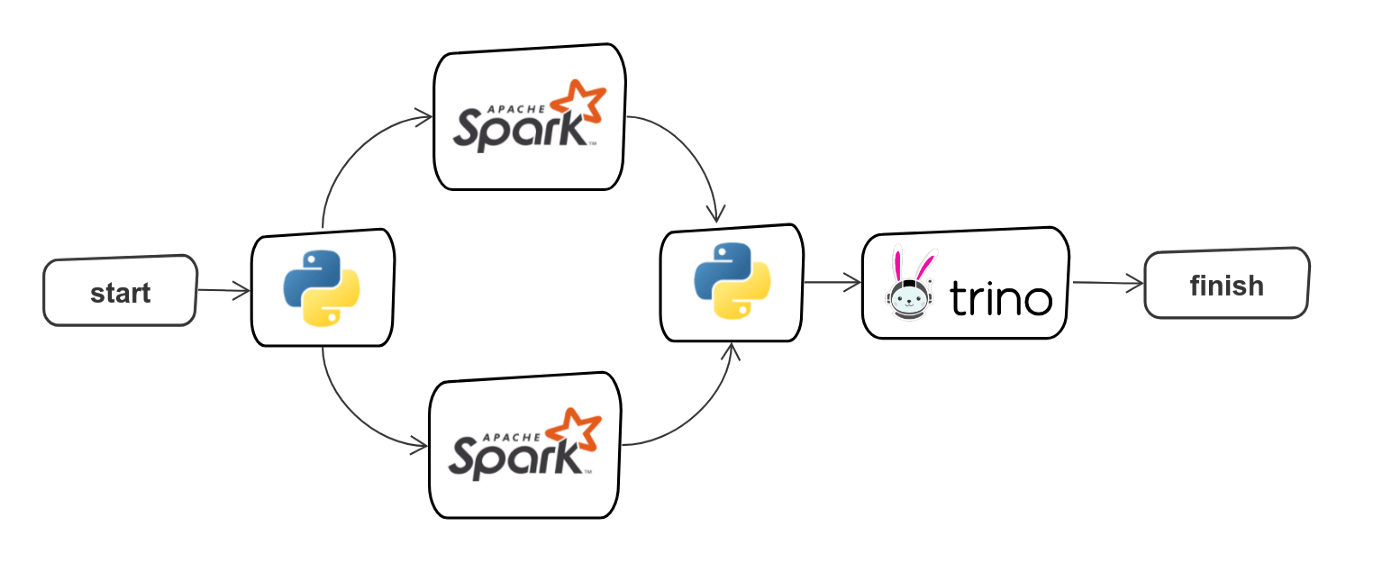

In the presence of computation jobs on engines like Spark, Hive, Trino, and lots of Python code for data processing and ML frameworks, workflow orchestration grows into a complex challenge. Orchestration is the mechanism that puts computation tasks together and executes them as a data pipeline, where the data pipeline usually looks like a graph.

Example of a data pipeline

Example of a data pipeline

It is important to note that orchestration is not the computation itself. Typically, we orchestrate tasks that are performed on external compute clusters.

Historically, Lyft has used two orchestration engines: Apache Airflow and Flyte. Created and open-sourced by Lyft, Flyte is now a top-level Linux Foundation project.

At Lyft, we are using Airflow and Flyte: engineers may choose the engine that better fits their requirements and use case

Both Flyte and Airflow are essential pieces of the infrastructure at Lyft and have much in common:

- support Python for writing workflows

- run workflows on a scheduled basis or ad-hoc

- provide integrations with compute engines

- work well for batch and not suited for stream processing

We shared our experiences with Airflow and Flyte in the previous posts. In this post, we will focus on comparing their implementation at Lyft. First, we dive into the architecture and summarize its benefits and drawbacks. Then, we tell why Lyft decided to create Flyte while already adopting Airflow. In the end, we share our thoughts on the patterns and anti-patterns of each engine and provide example use-cases.

We hope this information helps you choose the appropriate engine based on the requirements and specifics of your use case.

Airflow

Apache Airflow is an orchestration engine that allows developers to write workflows in Python, run and monitor them. Today, Airflow is one of the essential pieces of our infrastructure. Lyft is one of the early adopters of Airflow, and we have contributed several customizations, security enhancements, and custom tooling.

The main problems Airflow solves at Lyft are orchestrating ETLs by marshaling SQL queries to compute engines like Hive and Trino

Airflow concepts

For better context, here are a few key concepts of Airflow:

- Task: a unit of computation. Tasks within one DAG can be executed sequentially or in parallel.

- DAG: directed acyclic graph — a workflow composed of tasks and dependencies between them.

- Operator: the archetype of a task; for example, a Python / Bash execution or an integration with a compute engine like Hive or Trino.

- Sensor: a subclass of the operator responsible for polling a data source and triggering DAG execution. The most popular sensor at Lyft is the partition sensor which polls Hive tables and triggers when a new data partition is added.

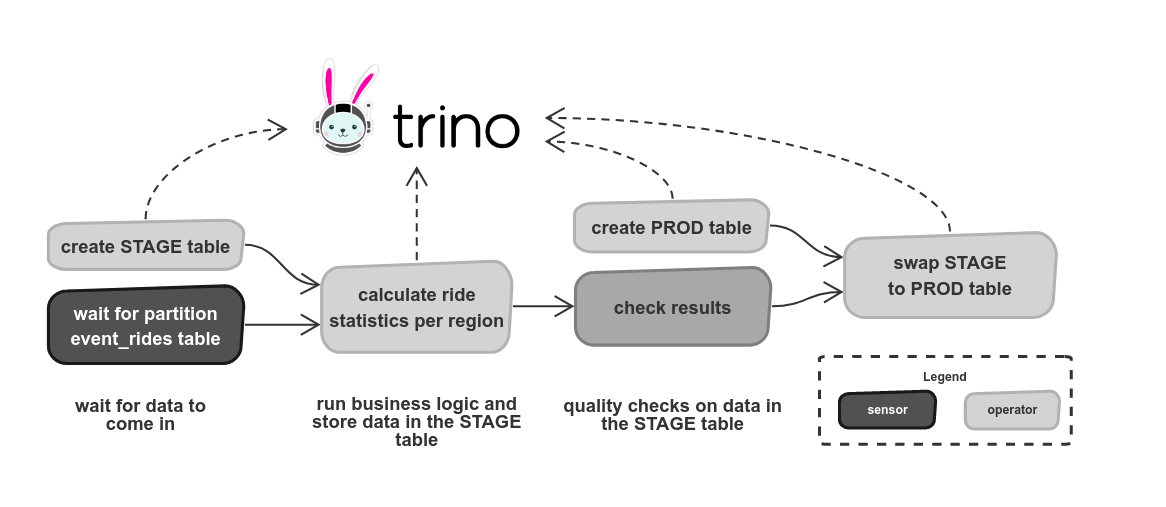

Example Airflow DAG (directed acyclic graph)

Example Airflow DAG (directed acyclic graph)

The partition sensor continuously polls the “event_rides” table and triggers when the previous day’s rides appear. Then ride statistics are calculated and stored in the STAGE table. After checking the correctness of the results, the data is swapped with the previous PROD table.

Please refer to the documentation for a more detailed background on Airflow and a complete list of operators.

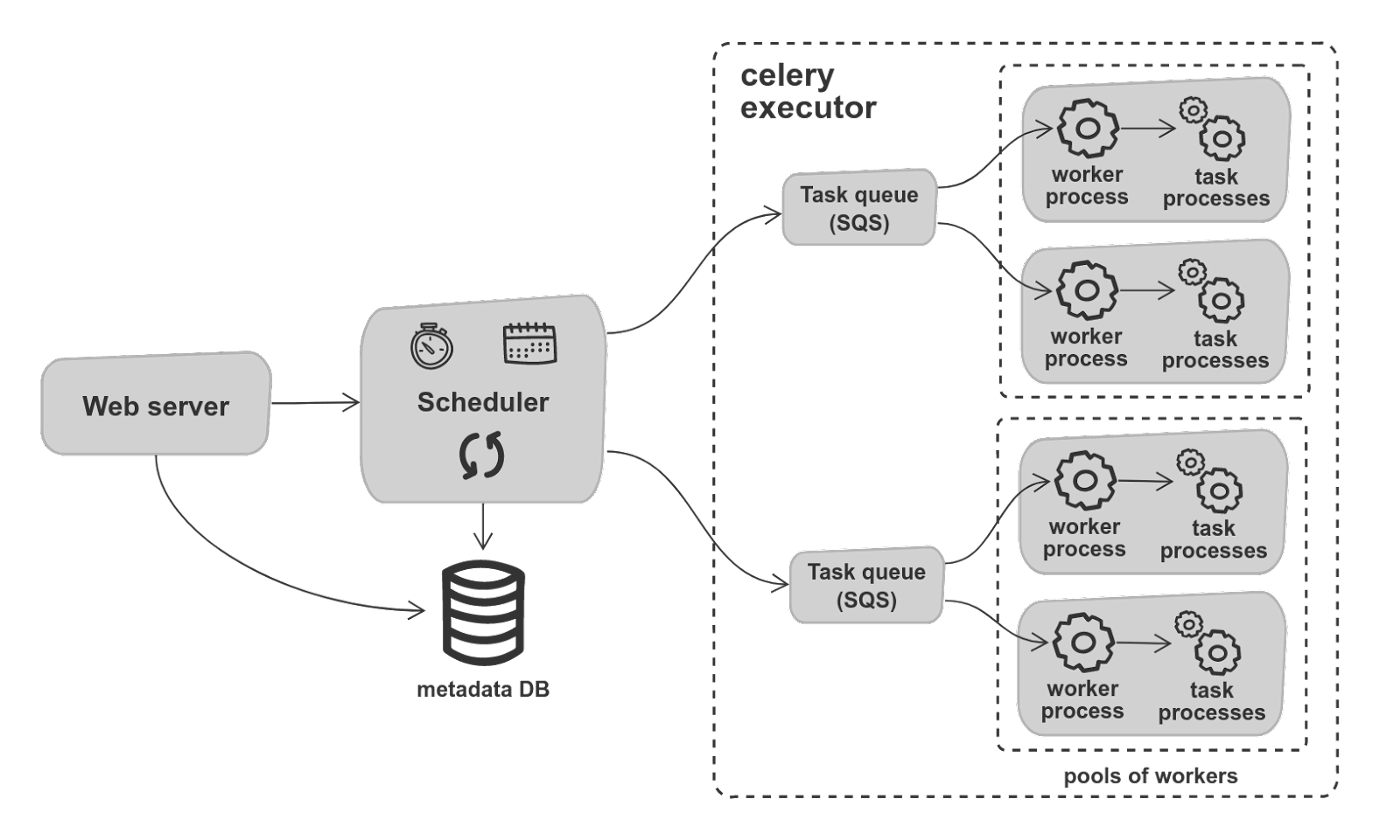

Airflow architecture at Lyft

Airflow architecture at Lyft

Airflow architecture at Lyft

As listed in the above diagram, the primary architecture components are:

- Scheduler: runs DAGs, sends them to the executor, records all completed executions in the Metadata DB.

- Web Server: a web application that allows triggering DAGs, viewing their status, and execution history.

- Celery executor: message queues and the number of workers which run tasks as separate processes.

At Lyft, we use Apache Airflow 1.10 with an executor based on a celery distributed task queue. This is a centralized monolithic batch scheduler with a number of workers that can be scaled horizontally. All machines must have an identical set of libraries with similar versions. It’s important to note that workers execute tasks as separate processes on the same machines. We are sharing our experience related to version 1.10 of Airflow in this article as we are still in the process of moving to version 2.0+.

Airflow benefits

Airflow is an easy-to-learn and quick-to-start tool. There is a vast open source community and good documentation. Airflow has a simple and intuitive web UI. What is worth mentioning is the extensive number of operators. Good support for table sensing tasks is another great benefit.

Airflow drawbacks

Below you can find the Airflow drawbacks that we found most significant for us.

- Airflow lacks proper library isolation. It becomes hard or impossible to do if any team requires a specific library version for a given workflow. Also, for ML, It is often a case when teams create their libraries and reuse them across multiple projects and workflows: model training and serving, which means all workflows have to run the same version of that library.

- There is no way to limit resource usage by task, also workers are not isolated from the user code. Therefore, resource-intensive tasks may overwhelm the worker and negatively impact other tasks. Heavy tasks can also stop other workflows from making progress as a fixed pool of workers may be fully consumed.

- Airflow does not support DAG versioning: we always observe the most recent version. Therefore, it is impossible to run the previous version in case of an issue or compare outputs of different versions.

- There is no way to separate DAGs to development, staging, and production using out-of-the-box Airflow features. That makes Airflow harder to use for mission-critical applications that require proper testing and the ability to roll back.

In addition, it is worth mentioning some nuances:

- At Lyft, all DAGs go to the same Airflow instance, and a logical workspace is shared across all teams. There are teams that work with sensitive data and have specific security requirements. The separation of security boundaries is only possible by maintaining a separate set of workers with different IAM roles. Always allocating separate workers makes it harder to maintain a more granular permission isolation per use case.

- Airflow doesn’t manage the data flow between tasks, the sequence of tasks should be defined explicitly. With Airflow not being data-aware, it is hard to implement caching as there’s no support for it. Finally, Airflow is designed for Python only and doesn’t allow writing workflows in other languages.

Flyte

Flyte is a workflow automation platform for complex mission-critical data and ML processes at scale. Currently, Flyte is actively developed by a wide community, for example, Spotify contributed to the Java SDK.

Apache Airflow is a good tool for ETL, and there wasn’t any reason to reinvent it. Flyte’s goal was not to replace Airflow but to complement the company’s tooling ecosystem. There were classes of problems where we were constrained while using Airflow:

- Use-cases utilizing custom Python, Spark code, or ML framework leading to a resource-intensive computation, requiring custom libraries. The library versions may be different across teams.

- Ability to run a heavy computation with no impact on other tasks.

- Ability to roll back and execute an older version of the workflow to compare the outputs and introspect.

- Support for results caching to speed up workflow execution, reduce cost.

At Lyft, Flyte is used for tasks that require custom libraries and compute isolation such as resource-intensive Python, Spark jobs and ML-frameworks

Flyte concepts

For better context, here are a few key concepts of Flyte:

- Task: an execution unit that has an isolated environment with libraries and packages. Tasks can be Python code, distributed Spark jobs, calls to a compute engine like Trino or Hive, or any Docker container execution.

- Workflow: a set of tasks and dependencies between them.

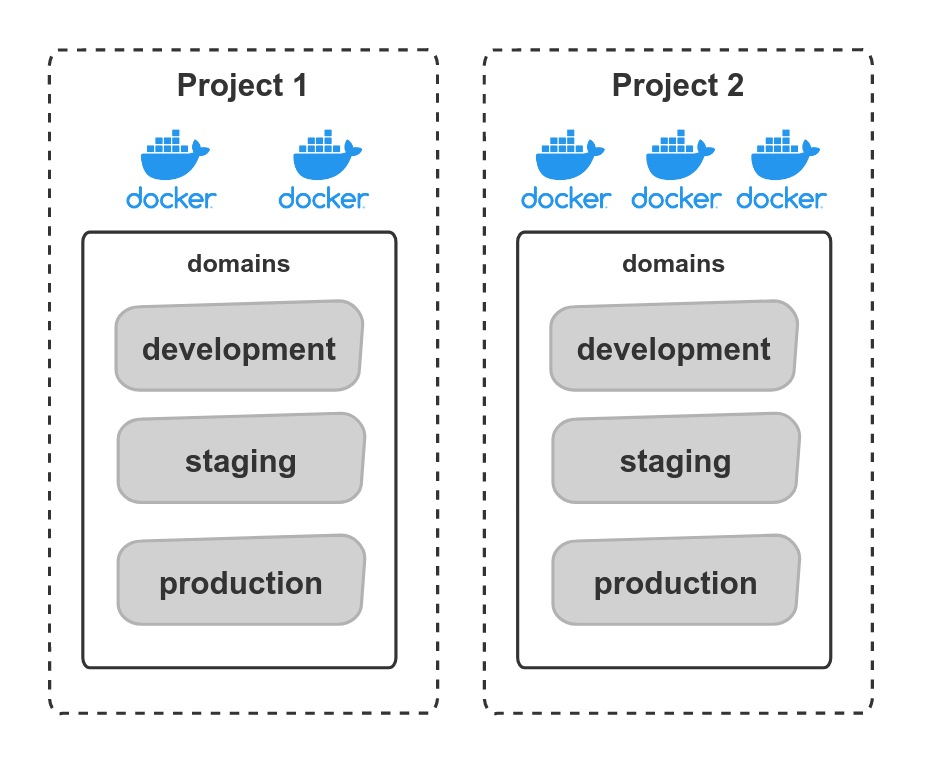

- Project: a set of workflows.

- Domain: a logical separation of workflows in the project: development, staging, production.

- Launch Plan: An instantiation for a workflow that can be tied to a cron and can use pre-configured input.

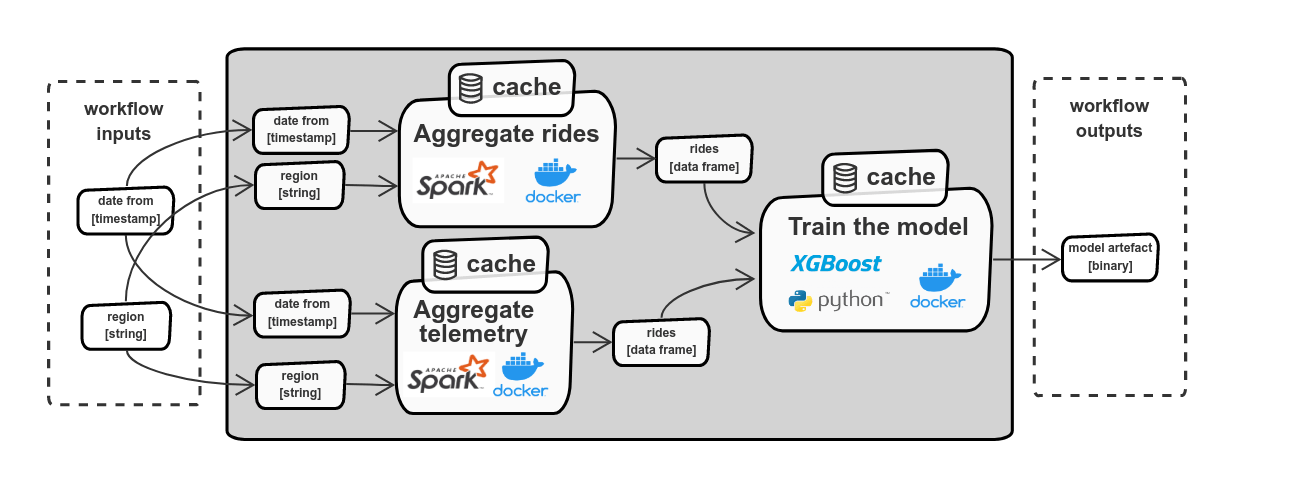

Example Flyte workflow

Example Flyte workflow

Example workflow composed of the two Spark tasks (“aggregate rides” and “aggregate telemetry”) aggregates data and produces output for the model training. The model training task contains a custom python code and XGBoost library packed as a Docker image. The final output is the model artifact.

Inputs and outputs of the workflows and tasks follow a strongly-typed schema. Flyte automatically detects dependencies between tasks based on inputs and outputs, builds dependency graphs, and automatically decides to execute tasks sequentially or in parallel (when using Airflow we have to explicitly define a sequence of execution). Having strongly-typed interfaces allow achieving interop between tasks or workflows created by different teams.

To know more about Flyte, its features and use-cases refer to the Flyte documentation.

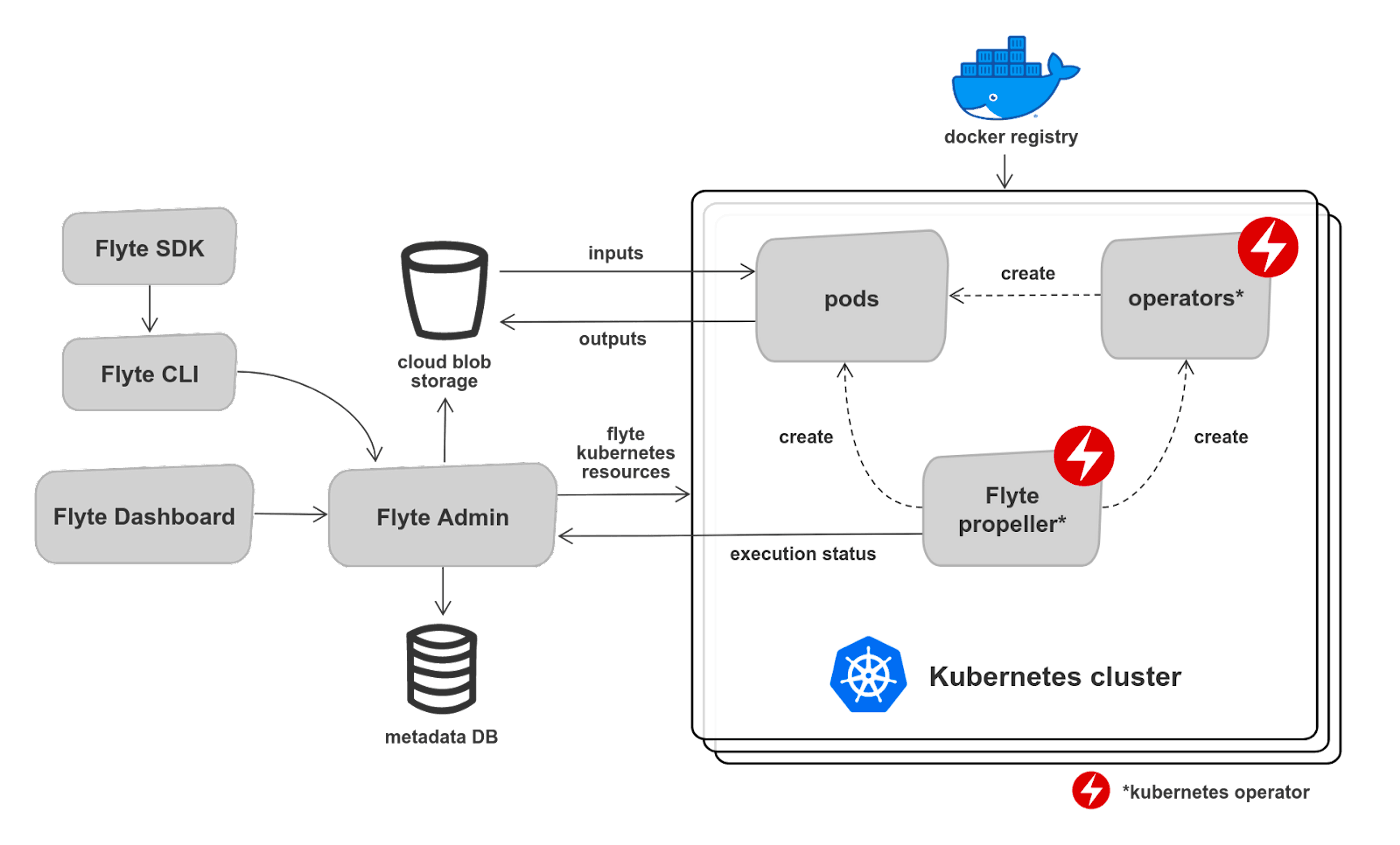

Flyte architecture at Lyft

Flyte does take some inspiration from Airflow but has some differences. Flyte adds a meta-layer on top of Kubernetes to make large stateful executions possible. Flyte is responsible for requesting resources and executing computations, for example, running new pods or Spark clusters. Kubernetes manages task execution and resource isolation. The infrastructure is ephemeral: created from scratch per task execution and then terminated.

Flyte architecture is based on Kubernetes operators and custom resource definitions (CRD). A good example is Spark on Kubernetes.

Flyte architecture at Lyft

Flyte architecture at Lyft

As listed in the above diagram, the main architecture components are:

- Flyte admin: a service that registers and stores workflows in Metadata DB. On triggering an execution it creates Flyte workflow resources (custom resource definitions, CRDs) in the Kubernetes cluster and records execution history.

- Flyte propeller: a Kubernetes operator that polls Kubernetes API looking for newly created Flyte workflow resources (CRD) and launches pods or other operators like Spark. It also handles failures and retries and does throttling and queueing if a Kubernetes cluster lacks resources.

- Flyte dashboard: a web interface that allows triggering workflows and to view the execution state.

- Cloud blob storage: stores task inputs and outputs and schema definitions. Unlike Airflow, Flyte doesn’t use a relational database for this purpose to avoid a bottleneck. At Lyft, we use AWS S3.

At Lyft, we use multiple Kubernetes clusters to isolate failure domains and scale-out. Flyte Admin supports this mode out of the box.

Flyte benefits

The primary driver of Flyte adoption was addressing some fundamental gaps in Airflow that were important to us.

The most significant advantage of Flyte is environment and dependency isolation. The code and libraries are packaged in a Docker image. Such an approach allows having different libraries with different versions per team or even doing it for a specific task. The project is logically split into domains: development, staging, and production. Domains allow promoting code to production step-by-step following development practices such as CI/CD, unit/integration testing, and code review.

Environment and dependency isolation in Flyte

Environment and dependency isolation in Flyte

Kubernetes allows defining resource quotas and achieving proper compute isolation. Resource-intensive tasks do not negatively impact each other and do not bring the stability of the entire scheduler at risk. Flyte is a good choice if your tasks have specific resource requirements, such as GPUs: Kubernetes routes such tasks to the nodes with GPU support. Moreover, we can do proper permission isolation between Flyte workflows: Kubernetes supports a concept of the service account and allows us to assign specific IAM roles per pod.

A compelling feature of Flyte is workflow versioning: we build a new Docker image with a new version of code and libraries, and register a new workflow version. We can run any version at any time: this gives us a tremendous advantage for debugging issues, rolling back the change, and comparing outputs between different versions (do A-B testing). The ability to use domains and workflow versioning makes Flyte a good choice for critical applications where changes should be tested and deployed agnostic of currently executing workflows.

Currently, Python and Java SDKs are available for writing workflows. Yet interestingly, Flyte compiles workflows and stores them in a language-agnostic representation, which allows us to contribute a new SDK and potentially add support for any language through raw containers. Flyte is perfect for heterogeneous workflows: we can package any binary executable as a Docker image and make it a task that gives us the flexibility to choose any language for development or any libraries/frameworks.

The other benefits of Flyte are worth mentioning, such as registering and running workflows via API and the ability to cache task results. Data awareness allows us to concentrate on business logic and let Flyte build a dependency graph for us.

Flyte drawbacks

The most significant Flyte drawbacks are related to cost:

- Flyte environment and dependency isolation come with a cost: teams need to maintain a repository, Docker images, and upgrade libraries. Some teams are fine not making this effort and find Airflow easier to use.

- Flyte creates ephemeral infrastructure in Kubernetes. Isolated on-demand ephemeral infrastructure brings additional time-spent costs of spinning up new pods and is excessive for small tasks or jobs. This is a tradeoff: the cost of spawning an ephemeral cluster vs. maintaining a standalone cluster. It doesn’t look like a Flyte problem but rather as an anti-pattern. By the way, the Flyte community is working on an update that will make it possible to re-use pods across tasks and workflows. That will allow us to run small workloads with lower latencies.

Flyte currently doesn’t have as many integrations as Airflow, which may require more manual work writing custom code.

Airflow vs. Flyte: choosing the right tool for your use-case

Lyft is a heavy user of Airflow and Flyte: currently, we have more than ten thousand unique workflows and about a million executions per month. We provide guides and encourage teams to use a recommended tool based on the characteristics of their use cases. We do not have strict rules at Lyft on when to use Airflow or Flyte as there could be many other reasons behind the team decisions, like historical usage or expertise in a particular tool.

When to use Airflow

Apache Airflow is a good tool for ETLs using a standard set of operators and orchestrating third-party systems when custom environment and compute isolation are not required

However, reconsider using Airflow if your workflow contains any of the anti-patterns explained below:

- Version locked dependencies: Airflow is unsuitable if you need customized dependencies or libraries. All DAGs in Airflow share common libraries. Everyone must adhere to the versions of those dependencies. It is hard to isolate dependencies between different DAGs.

- Resource intensive tasks: Airflow has a fixed number of workers that run multiple tasks at any point. The tasks typically hand over computation to external systems like Trino, but Python or Bash operators are run locally. Resource-intensive tasks may overwhelm worker nodes and destabilize Airflow.

- Pipelines with dynamic tasks: Airflow is not suitable for dynamic pipelines which change the shape of DAG at runtime using inputs or output of previous processing steps.

- High-frequency pipelines: Airflow is designed for recurring batch-oriented workflows. Frequencies less than several minutes should be avoided.

When to use Flyte

Flyte is a good tool for resource-intensive tasks which need custom dependencies, an isolated environment, and infrastructure

Reconsider using Flyte if your workflow contains any of the anti-patterns explained below:

- Small batches: Flyte creates infrastructure from scratch and terminates after task completion. It takes time to launch new pods, which adds additional expenses when we want to run small batches frequently. Use a static cluster instead of an ephemeral one for small tasks. Another option would be using a service-oriented event-driven architecture. If you still want to use Flyte, consider using caching if applicable.

- Table sensing is considered an anti-pattern for Flyte. Instead of polling a data source, use an event-driven approach and start Flyte workflows by calling the API.

- Complex parallel computations: Flyte provides map tasks and dynamic workflows but is not suitable for complex parallel computations when shuffling is required. Use a compute engine like Spark if you need data partitioning, distributed joins, or complex aggregation.

Example use-cases

We have identified two major use case classes at Lyft:

- ETL, mainly SQL: most of these workflows orchestrate queries to Hive or Trino and manipulate data in SQL tables using SQL statements. There can be a minor portion of non-SQL tasks like executing Python/Bash scripts to dump results to or from CSV on S3 or uploading results to a relational database. We usually use Apache Airflow for such use cases.

- Computation tasks requiring custom environments or libraries: Python tasks, Spark executions with custom libraries (for example, frameworks for spatial data processing), image/map processing, ML model training, etc. One is typically better off using Flyte. Below, we collected a summary and several use-cases that give you examples of distinguishing between two engines.

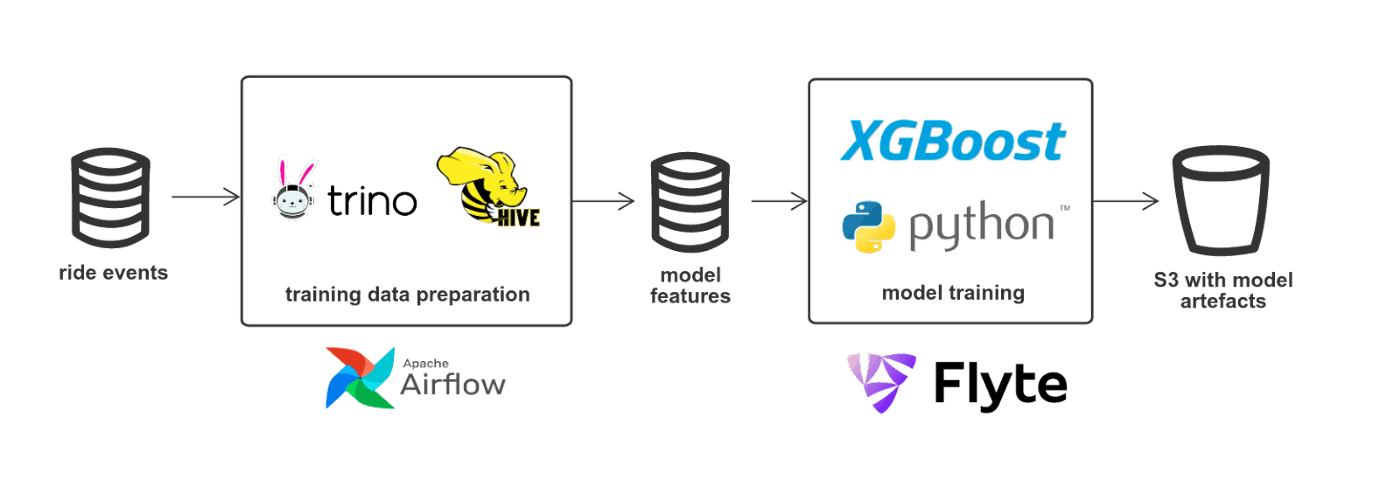

Pricing optimization to maximize rides and profits

Pricing is an incredibly powerful tool for achieving the company’s strategic goals, whether those are profits, rider growth, rider frequency, increasing density, or some combination of all of those. Because of the millions of pricing decisions Lyft has to make per day, we turn to machine learning for major parts of our pricing system. One important input to pricing is predicting the cost of serving a ride. This is done with a set of XGboost models. The end-to-end flow contains three major parts: training data preparation, model training, and model serving.

Pricing optimization model training

Pricing optimization model training

The training data preparation step is a set of ETLs that get events like rides, fares, taxes, tolls, etc., as input, perform a set of Hive/Trino queries and produce an inference data set with model features. The ETLs are running daily. We use Airflow because it is an excellent tool for powering ETLs that orchestrate external systems like Hive/Trino.

The model training step is a set of workflows that train the models and output model artifacts like the XGboost model to S3. We use Flyte due to the following reasons:

- We share a custom python code across workflows, using and building numerous libraries. We also need custom Docker images.

- We build deterministic tasks and leverage caching a lot: this makes us efficient and reduces execution time from multiple hours to under an hour. Some workflows may have 20–30 tasks. Once the task fails, we may fix the problem and re-run the whole pipeline: cached tasks will pass quickly. Caching helps us to reduce costs tremendously as well.

- Model training is more an ad-hoc process rather than scheduled. One day we may re-train 20 models, and other days we won’t train anything new. Flyte makes it more convenient to call workflows with different parameters.

- The ability to use separate environments: development, staging, production reduces errors, which can potentially have a significant impact on Lyft if caught in production. Doing so across a large number of ETL users on a centralized Airflow version will be a nightmare and massively slow us down.

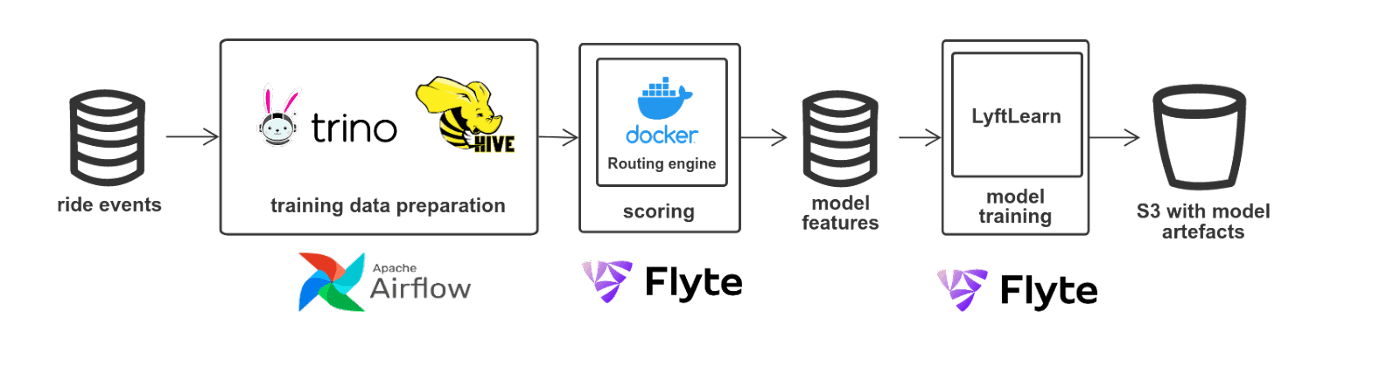

Prediction of the arrival time

The goal is to predict travel time from point A to B and show it when the user requests a ride. The ETA service relies on GeoBoost models to provide an accurate estimation.

ETA model training

ETA model training

For the training data preparation, we have ETLs that aggregate information about historical rides and already estimated arrival times by performing a set of Hive/Trino queries. Like in the previous use case, Airflow is used for this purpose.

Before we start model training, we do scoring of the rides data. We use a Routing engine component that computes routes based on road and speed information. A Flyte workflow runs a Routing engine packaged as a Docker container against the historical rides and does scoring. The results are then used as an input for the model training step.

We use a LyftLearn — in-house ML platform for the model training. Flyte workflows orchestrate model training and then perform model validation by running model predictions against the data set produced by the previous model version and comparing the results.

Providing market signals for price calculation

Efficient balancing of supply and demand is crucial for any ridesharing company. At Lyft, we perform real-time supply and demand forecasts. For example, we predict how many drivers will be available or how many rides will be requested in a particular area. The forecast data is used by different consumers, such as pricing models.

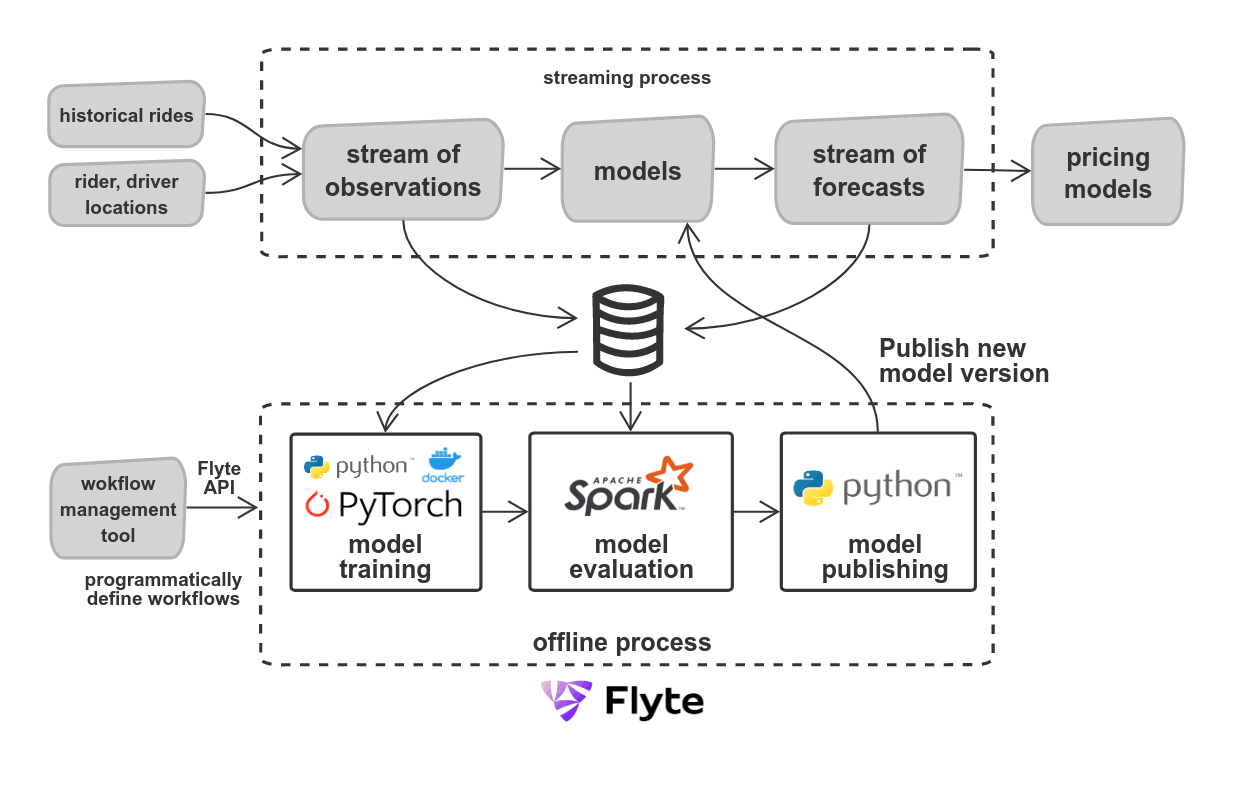

Supply and demand forecasting

Supply and demand forecasting

The system contains streaming and offline parts. The models consume a stream of events like rides and rider/driver telemetry and predict supply and demand, providing a stream of forecasts. The input and output data are stored for subsequent model training and evaluation. The offline part performs model training, model evaluation, and publishing. The product of the offline part is the live model, which is executed in the streaming process. We also perform a regular health evaluation of the models and produce metrics and reports.

We use Flyte as it provides environment and infrastructure isolation and the ability to register workflows via API and workflow versioning.

Versioning is essential as there can be cases where we can improve the model performance, but this may not translate to similar or equitable improvement in downstream business metrics for consumers. In effect, there could be multiple versions of the streaming model in production running simultaneously, and consumers may subscribe to the events produced by a particular version. This allows interop between teams as consumers may stay on the older version and perform A-B testing. Each model version is associated with a Flyte workflow version and is labeled with a GIT commit SHA.

Flyte provides an API that allows the creation of workflows programmatically. It enables us to dynamically build a complex ecosystem of supporting offline workflows for models without the model developer having to think about it. We built a workflow management tool that allows us to automatically create Flyte workflows once we introduce a new model version.

Keeping map data accurate and fresh using computer vision and GPU

We do imagery processing to recognize objects on the road like road signs and traffic cones. Then, we use the information about the identified objects to enrich the knowledge of the map, for example, determining road closures. The more accurate map data allows us to do a more optimal route calculation, better ETA, and trip cost estimation.

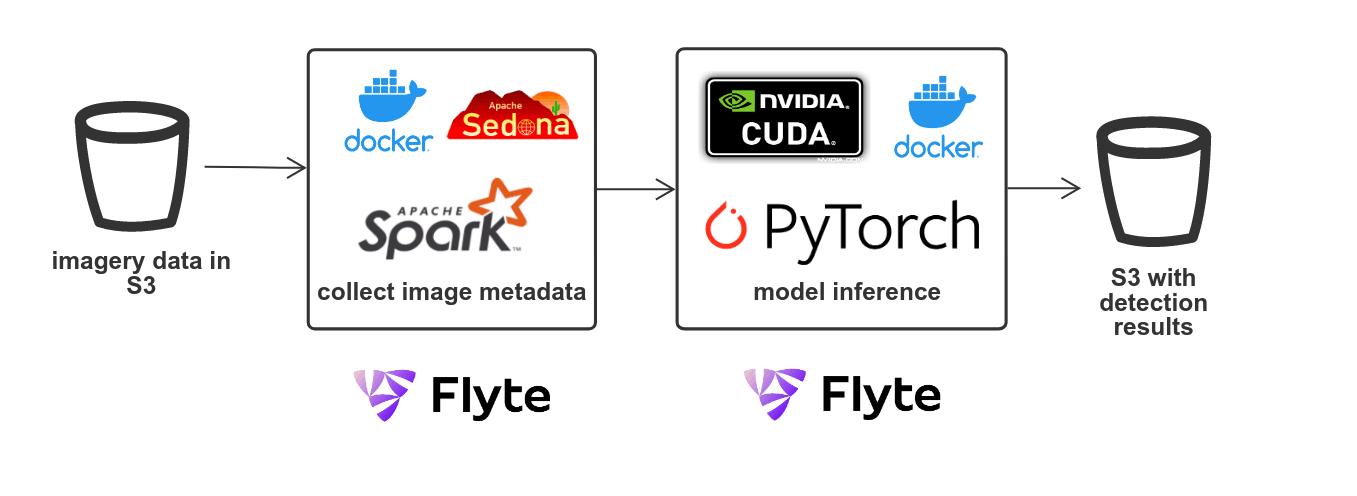

Image recognition pipeline

Image recognition pipeline

The process involves collecting imagery metadata and using computer vision ML models on PyTorch. The model execution requires resource-intensive GPU computations. Flyte is used for the whole pipeline as it allows us to leverage Kubernetes capabilities for routing tasks to GPU servers when we need them. There is also a need to customize the Spark cluster with the libraries for spatial data processing, such as Apache Sedona that we include in a Docker image which Flyte Spark operator supports.

Conclusion

We shared how we use Airflow and Flyte to orchestrate data pipelines in this post. We covered various aspects of the topic:

- Airflow and Flyte concepts and architecture at Lyft, their benefits and drawbacks The limitations of Airflow that led to the creation of Flyte

- Recommendations of how to choose a particular tool depending on a use case class

- Several example use cases that illustrated the usage of Flyte and Airflow

Airflow is better suited for ETL, where we orchestrate computations performed on external systems. Therefore there is no need for compute isolation on the Airflow side. Furthermore, we are using a standardized set of libraries such as Hive/Trino client, so library customization is not required. A big plus of Airflow is that it is easy to learn and provides support for table sensing tasks. Many teams are using Airflow because it is quick to start, there is no need to maintain custom Docker images or libraries.

If custom environment and compute isolation are a concern, then Flyte may be a better solution. Flyte relies on Kubernetes, which provides such capabilities out of the box. The typical Flyte use cases are Python or Spark jobs which require custom libraries or ML frameworks. A substantial advantage of Flyte is workflow versioning. It is worth mentioning that customization and isolation come with a cost: teams need to support their Docker images. Ephemeral infrastructure brings additional excessive costs for short-lived tasks.

Choose the right tool based on your requirements and the specifics of your use case. Keep in mind that there will always be cases that can be implemented sufficiently well, on either of the two engines. There are classes of use cases like streaming where neither Flyte nor Airflow is suitable.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to the following people who provided feedback, ideas, contributed their use-cases and helped to create this post: Aaron TaylorMays, Anand Swaminathan, Anmol Khurana, Artsem Semianenka, Arup Malakar, Bhuwan Chopra, Bill Graham, Eli Schachar, Igor Valko, Ilya Zverev, Jack Zhou, Ketan Umare, Lev Dragunov, Matthew Smith, Max Payton, Michael Burisch, Michael Sun, Nicolas Flacco, Niels Bantilan, Paul Dittamo, Robert Everson, Ruslan Stanevich, Samhita Alla, Sandra Youssef, Santosh Kumar, Willi Richert.